It’s not news the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns accelerated an existing shift to digital financial services, including payments.

What’s the role of cash in financial inclusion?

The latest issue of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Finance and Development Journal carries an analysis of the shift. “The future of money is undoubtedly digital,” according to F&D editor-in-chief Gita Bhatt. “The question is: what is it going to look like?”

The IMF looks particularly at opportunities and potential risks of digital currencies but there is another critical dimension here: financial inclusion – writes Professor Steve Worthington.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) analysed this in a paper “Payments aspects of financial inclusion in the fintech era”. The BIS says “financial inclusion starts with payments as they serve as a gateway to other financial services, such as savings, credit and insurance”.

Unfortunately, the antonym of this claim is financial exclusion also starts with payments, especially when using cash as a means of payment.

The BIS describes access to and use of cash to be a “catalytic pillar” for financial inclusion and “the availability and acceptability of cash requires its physical production, its distribution by the private sector – banks and ATM providers – and merchants to accept it.”

Risk of exclusion

Those in danger of exclusion without convenient access to and acceptance of cash include “senior citizens, individuals with disabilities, undocumented migrants, people living in or moving out of extreme poverty or homelessness, the inhabitants of rural and remote areas and those with limited financial capability”.

Australia has considerable numbers of people in these groups at a time when there is an ongoing reduction in the availability and acceptability of cash.

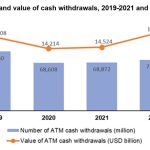

The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimates 2.5 million Australians live in regional or remote areas in Australia and the Australian Payments Network reported in June 2022 there were 25,168 ATMs in Australia – the lowest number in 16 years. ATM numbers peaked in the December 2016 quarter with 32,879 machines.

Financial inclusion is a global issue.

According to European Union research the main barriers impacting access of older people to basic financial services can be summarised into three categories:

- Age limits

- Digitalisation

- Poverty or low income

The research aims to ensure the financial inclusion of older people which benefits the individual, the family unit and broader society.

Participants in the study highlighted the many impacts of exclusion and they were consolidated into three categories: reduction or loss of financial and social autonomy; reduced quality of living in terms of access to goods and services as well as a negative impact on self-image and mental health.

These impacts can be observed by the correlation between older generations and a vulnerability to online fraud and scams. Respondents indicated older populations were often targets of fraud due to their lack of financial literacy and digital skills.

Disappearing cash

The EU report concluded by placing cash as its first necessary product for financial inclusion and recommended cash be maintained as a viable method of payment.

Yet cash is disappearing. The declining availability in Europe of both bank branches and ATMs, particularly in rural areas, is a major issue of access to cash for older Europeans who tend to prefer in-person transactions.

Mobility issues faced by older and disabled members of society also need to be considered, as does minimum withdrawal amounts which need to be set low enough so individuals on low incomes can use ATMs.

Of course, digital banking, well implemented and communicated, can also be powerful in addressing issues of physical accessibility.

Besides ATMs there are alternatives to cash access such cash back at retail outlets, banking services in post offices and neutral ‘branches’ shared by financial services providers.

But underlying this is a premise cash will continue to be accepted by merchants or utilities – and this is already not always the case.

In the United Kingdom legislation is being prepared that will enable the financial regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, to intervene to ensure communities are not cut off from banking services. The aim is to ‘set out’ expectations for a reasonable distance for people to travel to deposit and withdraw cash.

In some markets cash is not the answer to inclusion nor are legislation and regulation the only approaches to delivering inclusion. The example of M-PESA in Africa demonstrates this.

Launched in Kenya in 2007 by Vodafone and Safaricom (the then largest mobile network in Kenya), it has since expanded to Tanzania, Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa and Lesotho.

By March 2022, M-PESA had 52.4 million customers and it was the most successful mobile phone based financial services provider in the developing world.

Striving for inclusion

M-PESA’s “Inclusion for All” strategy has given people in formally cash-based but often unbanked societies access to the formal financial system. It allows users to deposit, withdraw, transfer money, pay for goods and services and access credit and savings, all with a mobile device.

Customers register for the service with authorised agents, such as mobile phone stores or other retailers, then deposit cash in exchange for digital money.

Ultimately, the aim for payments policy should be inclusion. Inclusion delivers benefits across society. It does seem inevitable cash will continue to decline in use, probably at an accelerating rate.

So it is essential that shift is managed to ensure it does not increase exclusion. With particular regard to those more vulnerable members of society who have been significant users of cash.

Paradoxically however, cash as a store of value continues to have a strong attraction to Australians. The Reserve Bank of Australia, releases monthly statements on how many banknotes are on issue and their value.

At the end of August 2022 banknotes to the value of $102,414 million were in ‘circulation’, of which just under 94 per cent were either $50 or $100 notes.

So, whilst accepting cash is being used less in payment transactions, it still is attractive as a store of value. Cash of course continues to have its own Triple A of attraction; it is Accepted nearly everywhere, it requires no Authorisation and it is Anonymous.

Why then should we deny access to cash and limit its acceptance as a means of payment?